Britishness: a disclaimer

Do you know how the Isle of Man voted in the EU referendum? Do you know how the people of the – unfairly stereotyped as — backward island in the Irish sea felt? You may guess, but do you actually know? No, and neither do they: they weren’t allowed a vote. That’s something we discovered when we visited to talk about the book, and visit their pier a week or so ago.

There’s something about visiting places that are a little out-of-the-way to make you look back at your country with fresh eyes. Counting up another 80,000 people disenfranchised by the government was another scale that fell. We’ve mused a lot about ‘Englishness’ over the last couple of years, and it’s disconcerting that as we’ve been able to understand a little more about what it means to us (and it’s a complex and cloudy beast, a mirror best approached from the side unless you want a shock), lots of other people have thinking too. They are surer, more forceful and as often with the confident and loud; wholly and widely wrong.

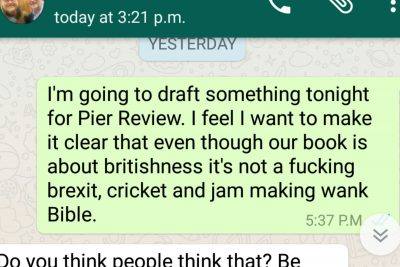

When Pier Review acquired the subtitle ‘A Road Trip in Search of the Great British Seaside’ — it came from the publishers who thought it explained a little what type of book it was — we were unsure at first. But now we like it: it’s silly and epic in equal amounts. But in the last year or so the idea of Britishness has been hijacked. Britishness now is a cypher and a shibboleth, a cloak within which people may warm and conceal their abhorrent values. It’s a love for something that is measured by your hate for anything other than itself. British values now seems to mean listing non-British workers, tacit permission to attack people based on appearance or the sound of their accents, and having schools register non-UK born students.

It seems like we shouldn’t have to make it explicit that when we refer to ‘Britishness’ in the title of the book, we aren’t referring any of that disgusting jingoistic shit but to a shared memory of the seaside, be it through direct experience or cultural references open to anyone with a library card or a television. For those that read the book, that’s hopefully an easy thing to take away: you won’t need the ‘Pier Review York Notes’ to know we’re exploring a place through our memories. But in case you haven’t yet picked it up, it might be worth knowing already.

Nostalgia is a tricky thing and our interest was in exploring where nostalgia and facts overlap with geography, to examine if this ideal notion of the seaside ever really existed at all.

Unfortunately the same things that make nostalgia interesting are the things that make it easy for it to be used as a tool by an increasingly fascist government. A government — and a large swathe of the extra-governmental political class — happy to use nostalgia as a way of pointing to something that never existed in the first place, telling a country of news-weary but fact-starved people who the reason we don’t have whatever it is that they want is minority groups or evil foreign power structures. The message is that all we have to do to get ‘it’ back is to submit to the views of a political minority and tacitly repeat the rhetoric of the power structure.

We drove around the country: it’s not full.

The government won’t, councils can’t, and business don’t see enough profit in doing anything to build the housing we need.

Our services are not strained by demand, they’re being purposely underfunded.

We’re not being overrun, infiltrated, or invaded. With every person or idea that joins us, we’re being strengthened .

It’s odd to be particularly proud to be English any more than to be proud of your shoesize. But if you wish to be, it would be flatter us that the country was a beacon for those less fortunate: that our status was an aspiration, and that our luck could be shared.

So if you’re looking to the book as some sort of jolly-hockeysticks-tweed-fox-hunting-keep-calm-and-make-some-fucking-jam-rose-tinted wankfest look elsewhere.

Our Britain is one where The Good Life taught us that two opposing ideologies can live blissfully next door to each other, where Porridge taught us that decency, tolerance, and friendship will get you through the toughest of times, and where Alf Garnet is the punchline not the hero.

Britain is diverse and as such we don’t share too many traits, but if you follow history one thing does stick out. Anytime our ruling class get too oppressive or unjust we rise up against them. From Winstanley’s simple thoughts that the land belonged to each one of us, to Tony Benn asking the powerful ‘how do we get rid of you’?, from Peterloo to Cable Street, from the peasants’ revolt to the poll tax riots, you can push us: but only so far. Riots are our binding birthright and bricks are our heirlooms.

Maybe that’s why they seek to divide us.